Guest post by Molly Tumusiime, Program Associate (Community Engagement), EngenderHealth/Uganda

The Right to Health asserts that people are entitled to access reproductive health services, including family planning (FP), that are acceptable to them and of the highest possible quality. However, there are many barriers to individuals’ realizing this right at many levels. While policy change and provider training can support increased FP access and use and better ensure contraceptive choice, interventions at the policy and service delivery levels alone are insufficient. Community-level barriers also impede service utilization and should be addressed in participatory and cooperative ways.

In 2010, EngenderHealth began piloting site walk-throughs (SWTs) in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Ghana, Tanzania, and Uganda. This promising approach—rooted in the core human rights principles of participation, empowerment, and accountability—catalyzes community participation in health and strengthens the accountability of service providers to communities. In addition, SWTs foster linkages and collaborative partnerships between health providers and community members in addressing barriers to informed choice and service access and in improving the quality and acceptability of services.

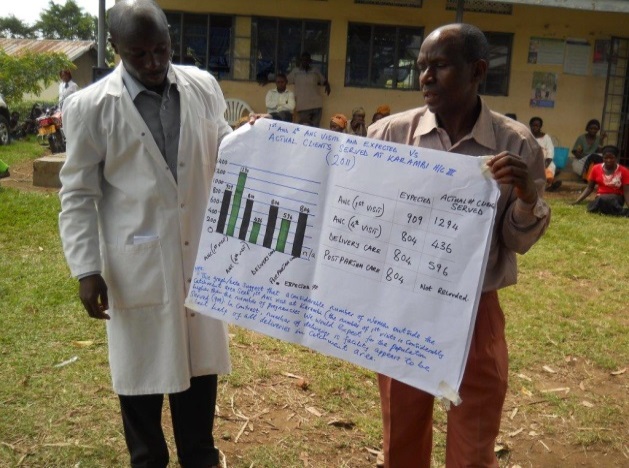

An SWT is a “guided tour” of a health facility for community representatives living in the site’s catchment area. Focusing on specific services, such as FP, the SWT provides an opportunity to sensitize influential community members about the health benefits of these services and to raise awareness about the range of available methods. Service statistics that highlight the gap between expected use of services (based on Demographic and Health Survey data on the demand for FP in the catchment population) and actual service use (based on caseloads) are used as a starting point for exploring community perspectives on barriers that prevent women and couples from accessing services and realizing their right to contraceptive choice.

Based on priorities identified by community representative and the health staff, action plans are developed to address barriers to access and use, both at the community level and at the health facility. These include a range of demand-side issues, such as lack of knowledge about the benefits of FP and about the availability of certain methods, as well as inequitable gender norms that constrain women’s ability to use FP and community concerns related to interpersonal dimensions of care and service quality (e.g., providers’ interpersonal communication skills, client privacy and confidentiality, etc.).

Preliminary results from the pilots indicate that SWTs increased overall use of FP services, broadened the contraceptive method mix, and strengthened the rapport, understanding, and teamwork between community leaders and health facility staff. “[The SWT approach] has improved [our] sense of community ownership,” said one Ugandan facility manager. “They know that the services that are offered here and the health center itself are theirs.” A community representative in Ethiopia was equally empowered: “The [SWT] has let us know the range of services available at the facility, the commitment and effort of the staff to improve quality of services, and [it] has changed our stance about the facility.”

Champions4Choice would like to like to feature other promising practices to ensuring that rights are respected, protected, and fulfilled in FP programs. Submit your guest blog post here!